(donations)

Joining the Hunt for the USS

Alligator

became an obvious decision for Alice M. Smith because the prototype’s

trials tested in the waters around her hometown as early as 1859.

A local bicentennial book mentions the

diving boat/submarine visits. The crew names were familiar, too.

Her job was tracking the crew and their

descendants—research further supported by Civil War pension records.

If she didn’t know them, someone else

did. Proof of the existence and location of the 1859 prototype boat

turned up in a letter by Henrietta Leon Bucher about her father’s

involvement with the submarine.

In 2005, when local newspaper printed the

story about the submarine search, men between the ages of 40-60 shared

their childhood memories of seeing a rusted hull hidden among the

phragmite and splatter dock along the creek. Frank Astemborski, at the

age of twelve, remembers ghastly tales told by the older boys.

One such tale scared Frank into

believing that dead men were hidden inside. He recalls peering

reluctantly through the glass ports to get a glimpse of the horror

hidden inside.

“Mud Duck” Eldridge, while searching

for muskrats, remembers seeing the prototype’s hatch. And Rich Pattanite

recalls leaping from the Tarzan swing and landing on a rusted hull.

Years have passed, but the search

continued along the creek and marsh area as we retraced the haunted

hunting grounds of the young boys.

With a team of volunteers we conducted eleven

expeditions with side scan sonar and a magnetometer.

In March, Stockton University’s

professors Steve Nagiewicz and Mark Sullivan surveyed using a Phantom 4 Pro V2.0 with Drone Deploy (Flight and Analysis). In the

report it was determined that there are two suspicious anomalies in the

area. It is our firm belief that Henrietta’s letter is accurate–the

submarine prototype and de Villeroi’s first 1835 submarine rest in the

same area.

To verify their existence and take the next steps towards eventual

recovery requires larger-scale aerial magnetometer scans. This is the

point we are at today—raising funds to pay for such work. To find these

craft would be an incredible boon to our understanding of period

technology and the earliest days of submarine warfare.

|

|

|

| Professors Nagiewicz and Sullivan deploying a drone | Target areas along the creek |

(excerpted from Natural Genius)

(return to the synopsis)

We

are taught that USS Holland (SS-1) in 1900 was the first modern

submarine in the U.S. Navy. This is true—but this was not the first boat

to interest that service. There was, in fact, a submarine active in

naval operations almost four decades earlier. The first submersible

deployed to a combat zone—with an enlisted crew under the Cape Hatteras

while under tow on a new mission—Alligator was the focus of a

concerted effort beginning in 2002 by the modern Navy to locate her.

After several years, it became apparent that her location and condition

would remain elusive for the present.

Alligator, however, was not the first submarine examined by the

Navy. That laurel belongs to her predecessor, which researchers dubbed “Alligator

Junior” on account of her smaller size. Built in 1859 for salvage work,

her inventor offered her to the navy not long after Fort Sumter was

fired on. She is now the subject of an effort to pinpoint her location

and, hopefully, to begin recovery. Such a project would be far simpler

than finding Alligator, which may lie anywhere from 250 to a

thousand feet below the surface. Junior, we believe, sits buried in the

muddy bank of a small stream off the Delaware River mere feet below the

surface. Locals claim parts of her were visible in the early 1960s.

Alligator Junior and Alligator proper were the brainchildren

of Brutus de Villeroi, an inventor and “Engineer of the First Class,”

born in 1794 in France. Among other interesting inventions, de Villeroi

demonstrated his first submarine in 1832. His three-man

bateau-poisson performed well

enough, but failed to meet the criteria stipulated by the French Navy

for use as a weapon. A second trial for the Ministry of Education in

1835 also came to naught.

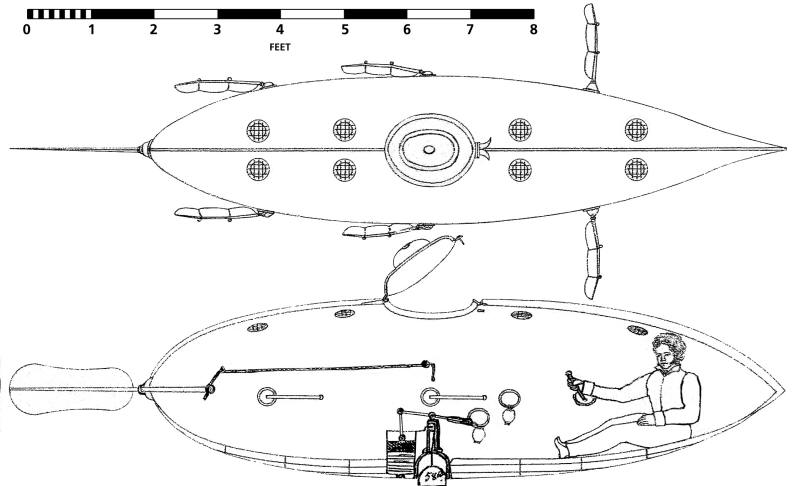

Plans

for this small ten-foot boat survive and indicate some advanced

features. For one, de Villeroi appears to have designed a lower hull

that acted as a ballast tank: his diagram shows a hollow space between

the outer skin and inner wall of the boat with an interior pump and

hoses to exhaust water to the outside. Although not shown in the

primitive schematics, reference is made to an early, but effective,

means of purifying the air of deadly carbon dioxide. This was a simple

“bucket and bellows” system, where spent air was forced across a

container of slaked (watered) lime, which captured and retained the

deadly gas but allowed the non-lethal components of breathable air to

recirculate.

Plans of de Villeroi's 1835 "fish boat"

Following the disappointing official reactions to his invention, de

Villeroi turned his hand to other inventions—but did not abandon his

hopes of marketing a working submarine. Immigrating to the United States

in 1857, he settled in Philadelphia. In September of that same year,

word spread along the eastern seaboard of the loss of the steamship

Central America in the waters off South Carolina. Four hundred and

twenty-three passengers and crew went down with her—as well as an

estimated $2.4 million in gold. Salvage operators were quick to approach

the underwriters of the lost ship, offering a variety of plans to

retrieve her incredibly rich cargo. These included sending divers down

to manually bring up the chests, schemes to patch whatever hole might be

found in her hull and pumping out the water to refloat her, and sending

down a submarine. In hindsight, none of these plans were in the least

practicable due to the depth at which the Central America rested.

Believed at the time to be a mere 168 feet below the surface, she was,

in reality, some 7,200 feet down, well beyond the reach of period

technology. Ignorance of this fact spurred a group of investors in

Philadelphia to bankroll Brutus de Villeroi to build a salvage submarine

for the operation. On 28 July 1858, John D. Jones, the president of

Atlantic Mutual, signed a contract with de Villeroi to retrieve the lost

gold.

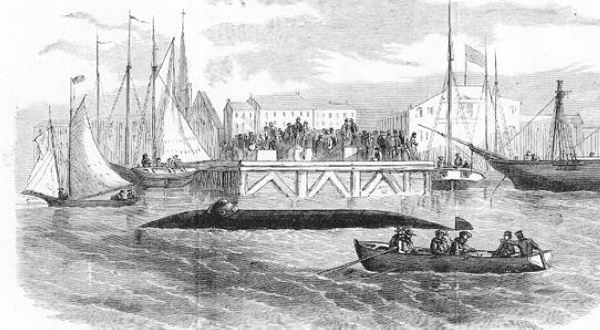

The new boat was first seen on 25 August 1859 off New Castle, Delaware, some 45 miles below Philadelphia. Described as “perfectly round” down the length of her thirty-five foot hull, she was a long and narrow vessel, measuring but forty-four inches in diameter. The interior was illuminated by a double row of bulls-eye deadlights embedded in twin rows along her back. One hatch on the top allowed the crew of, reportedly, a dozen men to wriggle in and out, while a second hatch amidships on the bottom afforded divers a means to exit and reenter the submerged boat. A three-foot propeller pushed the submarine through the water, and she could be made to rise and fall by angling her bow planes. These were plates of iron about eighteen inches square, which “are moved like the fins of a fish.

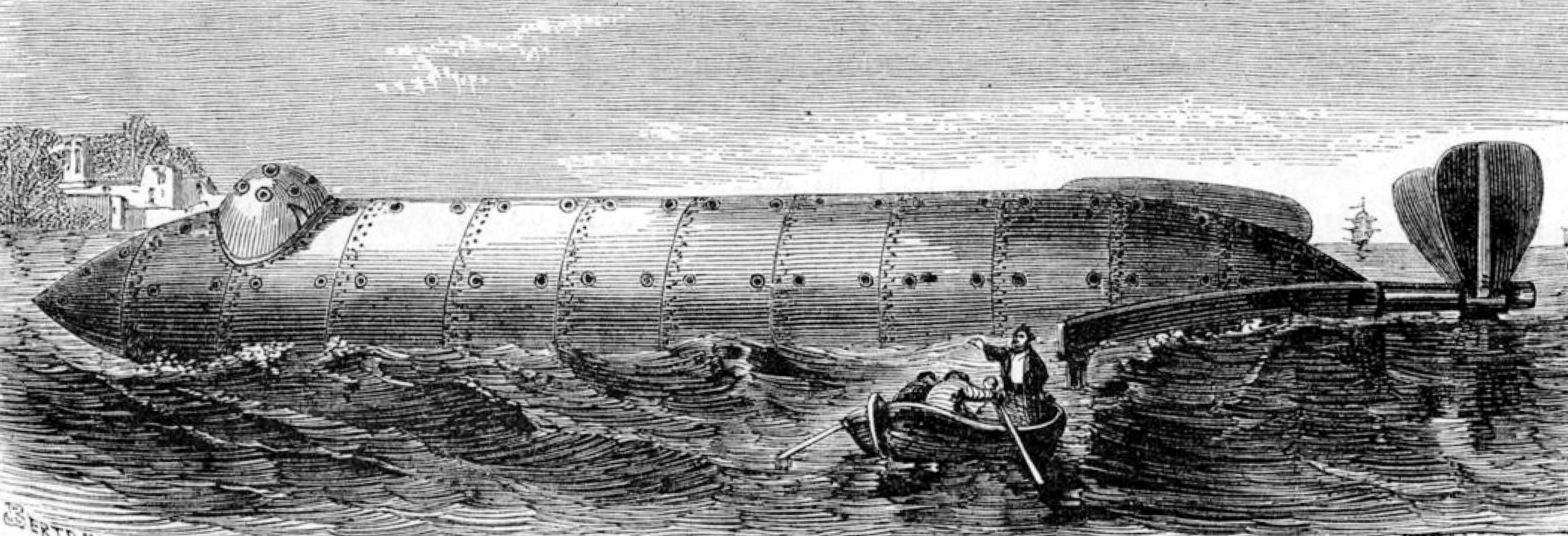

A wildly oversized representation of de Villeroi's salvage submarine from a French journal of the time

These bow or diving planes were

something unique. Such devices have been a commonplace in modern

submarines for over a century, but who first thought of the idea? Their

use seems very obvious today, but we must remember that early submarines

evolved from diving bells. These were used almost exclusively for

vertical movement, and had to rely for any lateral motion upon a surface

support boat. When the bells became enclosed and carried their own air

supply, the notion of diving or surfacing while underweigh was not

obvious: it was enough that the vessel could submerge in place to a

desired depth and then move about horizontally; if it became necessary

to sink further or rise a bit, more or less water could be admitted to

the ballast tanks. No submarine prior to 1859—and many for several years

thereafter—had diving planes. These include de Villeroi’s own 1832

bateau poisson; Bauer’s 1851

Brandtaucher; Phillip’s 1852 Steering Submarine Propeller; Bauer’s

1856 Seeteufel; Monturiol’s 1859

Ictineo I; Brun’s 1863

Plongeur; Monturiol’s 1863

Ictineo II; Merriam’s 1863

Intelligent Whale; and Kroehl’s 1864

Explorer. Interestingly, in

the impending civil war, Southern submarine designers would incorporate

bow planes in the [1861?] “New Orleans Submarine,” 1863

Pioneer II, and 1864

Hunley; Northern designers

would not follow suit until Horsford's Soligo in 1864 (which was

never completed). It may well be that diving planes were first devised

by Brutus de Villeroi.

All of the foregoing was visible from the outside of the boat. Evidence for the interior came from interviews with the crew or, most probably, de Villeroi himself. No one was allowed to enter the submarine at this time, since, “the invention having not yet been patented, many of the details in the working of the boat are kept a secret.” However, a quick and rudimentary sketch made two years later by a reporter for the Saturday Evening Post, shows some helpful details; it also entirely leaves out equipment which was known to have been part of the workings of the vessel.

One such system that was described but not drawn was the arrangement for taking on and discharging water ballast, which was very different than what the inventor had previously designed. Recall that the inventor created a double hull in the lower half of his first vessel, which acted as a ballast chamber. For his 1859 boat, he used large canvas bags coated with gutta percha (latex) as his ballast tanks; water was pumped into (and presumably out of) these “by machine”—probably manual force pumps.

The double hull approach worked

well on the smaller boat in 1832, but enlarging this system to the 1859

submarine would have increased the weight and cost significantly. Using

waterproofed cloth bags resolved both problems—but one that nonetheless

came at a price. While saving weight and money, there was a dangerous

tradeoff in safety.

Known as “camels,” the canvas bags

that de Villeroi employed were more commonly used as floats. Carried

deflated aboard ship, they could be ringed around a sunken or foundering

vessel, inflated, and raise her over a sand bar or even off the bottom.

Originally made of wood, camels had been built of leather and, in the

1840s, rubber. With the introduction of gutta percha to the West in

1848, that material began to be favored. Gutta percha, which is derived

from the sap of the Malaysia isonandra tree, could be formed into any

shape when heated, and retain that form upon cooling. If rolled in very

fine sheets, it could be pressed into cloth, steamed to over 300

degrees, and result in a flexible and waterproof fabric. It offered a

great many advantages over rubber, and gutta percha camels were all the

rage in the world of marine salvage after 1850.

De Villeroi’s application of the bags, while unique, was not illogical: if gutta percha could be used to keep water out, it could also be used to keep water in. But, as the American salvor John Gowen discovered in his operations at Gibraltar in 1851 and again at Sebastopol in 1857, camels, whether of rubber of gutta percha, had a disconcerting tendency to pop under pressure. For the men on the surface working the pumps, this was frustrating; for a submarine crew, it would be deadly. Allow too much water in too quickly or under high pressure at depth, and the bags could easily rupture and flood the boat.

Mention was also made in the

initial report of a divers’ hatch. This was not an air lock. Such a

chamber, then as now, sectioned off a diver in a small compartment; this

could be flooded and an outer hatch opened, allowing the diver to exit;

upon reentering, the outer door would be sealed, the water in the

compartment exhausted with air pumped from inside the submarine, and the

inner hatch reopened, permitting the diver to rejoin the crew. Instead,

de Villeroi followed the example set by fellow French submarine designer

Payerne: the entire interior of the boat was pressurized and a hatch in

the bottom opened to allow men to leave and return. Whether such

pressurization occurred while the boat was still on the surface—the air

being pumped in directly from the outside—or was the result of opening

multiple canisters of compressed air once on the bottom, is not

indicated. Given that de Villeroi had suggested the use of canisters to

refresh the interior atmosphere back in 1832, and that these same had

begun to be used for pressurization (Payerne), this is likely to have

been the procedure.

As with the crew of

Auguste, that of de Villeroi’s Salvage Boat dispensed with the

typical submarine armor. This is proven by a report of a second

demonstration, which took place on Sunday 2 October 1859 off Marcus

Hook, Pennsylvania (about a dozen miles downstream from Philadelphia).

The writer recorded that

This term was most commonly applied to Greek sponge divers who, plunging into the balmy waters of the Mediterranean, could well afford to enter the sea au naturel. Beyond such temperate waters, however, divers faced a chillier prospect. John Gowen’s armor-clad divers at Sebastopol on the Black Sea complained of the cold at depths not greater than sixty feet. John Greene, a famous “naked diver” on the Great Lakes, was known to descend to depths of over a hundred feet—where the temperature hovered near freezing; it is difficult (even dangerous) to think of him doing so without the benefit of at least a suit of flannels. “Naked” might well mean simply “unprotected,” (i.e., by submarine armor). However clad, anyone leaving the submarine needed a supply of air; at the time, this could only be provided through a pump-supplied hose. Whether de Villeroi’s divers wore any sort of helmet or headgear to which a hose might be secured is unknown; although risky, they might simply have held onto the hose with one hand or clenched the end between their teeth. For safety’s sake, the air hose would have been wrapped together with a tether back to the submarine. The only hint at this time as to the procedure is that “the workmen get out, taking with them the means of obtaining a full supply of fresh air from the boat.” The simplicity of the arrangement is further evidenced by a later U.S. Navy report that states simply, “the divers, who, breathing by means of tubes attached to the boat are enabled to perform submarine operations.”

To allow the divers to get out, the submarine would, of course, have to be stationary on the bottom. De Villeroi used a simple anchor—a conical iron weight—that was lowered from the hatch in the bottom once the vessel was on site. While undocumented, the process would logically have been to first drop the anchor to stop any motion in the current. Achieving neutral buoyancy by expelling a quantity of water from the ballast bags would be the next step. Finally, the anchor cable would be drawn up until the Salvage Boat rode at an appropriate distance above the seafloor to allow the divers to exit and reenter—perhaps four or five feet.

The

means of keeping the air for both divers and crew fresh was kept secret,

“but it is believed to be by some chemical arrangement.” A variety of

chemicals for removing “carbonic acid” were well-known and routinely

used. De Villeroi’s desire to keep his “arrangement” confidential

suggests more that he had devised some mechanical means through which to

apply his chemicals of choice—perhaps a series of pumps and reservoirs,

more or less complicated than what Payerne had created, but along the

same lines—than that he had discovered any new

“chymicall liquor.” It may also be that, having never been shy about

sharing his inventions with the world with no thought to monetary

profit, the board of investors in the Salvage Boat (who were certainly

keen to realize a return on their investment) instructed him to keep his

mouth shut about all aspects of the new submarine; if so, the “means of

keeping the air fresh” could well have been nothing more than the tried

and true “bucket and bellows.” Nothing drawn or written provides any

further clue.

For this, his second submarine, Brutus moved away from the use of paddles or oars to provide motion. Instead he opted for a large, three-foot propeller. This was powered by six of the crew who, ranging down the length of the hull, pulled on a leather strap that ran along the outer edge of the vessel. This strap spun a large wheel fixed in a horizontal attitude to a post in the stern of the boat, which in turn rotated the propeller, probably through use of a simple bevel gear. Given the confines of the Salvage Boat, the “propeller men” probably knelt or sat on small benches, facing outward, in a staggered formation. De Villeroi, acting as captain “sits near the head” to operate both the diving planes as well as the rudder.

Following the early October demonstration, there are

no more recorded dives for the remainder of 1859 and all the way through

1860. No attempt was made on the

Central America. A subsequent article claimed that

At the beginning of 1861, de Villeroi moved the

Salvage Boat across the river to New Jersey. There is no stated

rationale for this, but it may relate to funding: the major investment

in the “grand desideratum for submarine operations,” as a rather

excitable Philadelphia reporter had initially christened the new marvel,

had not returned any profit. It is believable that an appropriate spot

for mooring the boat might have been cheaper on the eastern shore of the

Delaware. From all appearances, de Villeroi had managed once again to

devote time, energy and money in an invention he could not capitalize

on. Now 64 years of age, Brutus’s most recent undertaking might well be

his last. While famed in France, in the United States he had a poor

track record of stale and failed discoveries and inventions. Only

something miraculous could rescue his reputation. But there would be no

miracle for the aging chevalier—only

a catastrophic event that would thrust him one last time into the

limelight and secure for his greatest creation a place in history. Far

to the South, on 12 April 1861, Confederate forces opened fire on Fort

Sumter in Charleston harbor. The War of the Rebellion had begun.

This event moved Brutus de

Villeroi to offer the navy of his adopted country its first submarine.

The Salvage Boat that would soon come to the attention of the United

States Navy had, since its October 1859 appearance, disappeared from the

papers. Save for mention of its relocation to New Jesey about January

1861, we know nothing of its activities through all of 1860. In fact, it

appears that the boat was simply docked and no additional dives made. In

a letter of 4 September 1861, de Villeroi referred to “the last

experiments which have been made at New Castle and Marcus Hook.” This

sounds as though no further tests were made in the year after the

demonstration in October 1860. But, based upon the events of 16 May

1861, work on the boat evidently resumed soon after the start of the

war.

Philadelphia, like every city in

the North and the South, had been gripped in the war frenzy that

followed the attack on Fort Sumter. After a few weeks, a sense of

relative calm had returned, and “Philadelphia [was] now as quiet as in

the most peaceful times.” Nonetheless, the public was vigil, and someone

had directed the attention of the police

|

to the movements of [the] iron submarine boat, to which very

extraordinary abilities and infernal propensities were

attributed. At ordinary times its discovery would have resulted in little excitement; but, now, when men think and dream only of treason, its capture involved speculations and odd rumors, which entitled it to some degree of notice. [It] was said to be an infernal machine, which was to be used for all sorts of treasonable purposes, including the trifling pastime of scuttling and blowing up Government men-of-war. |

About midnight on the sixteenth, Lt. Benjamin Edgar’s Harbor Police noticed a skiff manned by two men push off from South Street wharf. They followed the boat to the lower (southern) end of Smith Island and confronted the pair in the act of transferring their cargo of pigs of lead into a submarine. The men, Alexander Rhodes and Henry Kreiner, were taken into custody and, at two o’clock in the morning, their “iron pet” was towed to the Noble Street pier, to which it was chained by the police.